AI "Music" and What Makes Us Human

A response to a recent article about an AI tool that generates "music", and a confession.

If you didn’t read about the atom bomb that went off in the music world a few weeks ago, you weren’t alone. A company named Suno released a new AI tool that allows users to generate a facsimile of any kind of music they can imagine, but barely a whisper could be heard from the music press. In fact, there was such a notable absence of think-pieces on this new AI that

wrote an article for in which he offered the atom bomb analogy.In his article, O’Malley articulates both his anxieties and his optimism about what the new AI tool might mean for musicians and music lovers. I was largely on side with what he wrote until I reached this paragraph, which follows a description of AI “music” as simply a set of emotional triggers:

“I’m not sure this is so different from ‘real’ music. After all, we humans aren’t some special or unique part of the universe. We’re just meat-bags that respond to stimuli. Music isn’t special either. We all know that music can elicit emotions with just its musical qualities: When there’s a big key-change that gives us goosebumps, we’re no different from a cat that has been spooked by the garbage truck or the neighbors slamming a door.”

There’s something here of Shakespeare’s Benedick glibly asking, “Is it not strange that sheep’s guts should hale souls out of men’s bodies?” In any case, who hasn’t heard this particular story before? This is the shared narrative of the modern rationalist: humans are mere cogs in the vast Rube Goldberg machine of the universe. This story’s acceptance into Western culture was gradual then sudden: its groundwork was laid over the course of the twentieth century, and then it burst into full bloom with the new atheist movement at the start of this century. One of its most well-known expressions comes from vanguard atheist Richard Dawkins:

“The universe that we observe has precisely the properties we should expect if there is, at bottom, no design, no purpose, no evil, no good, nothing but pitiless indifference.”

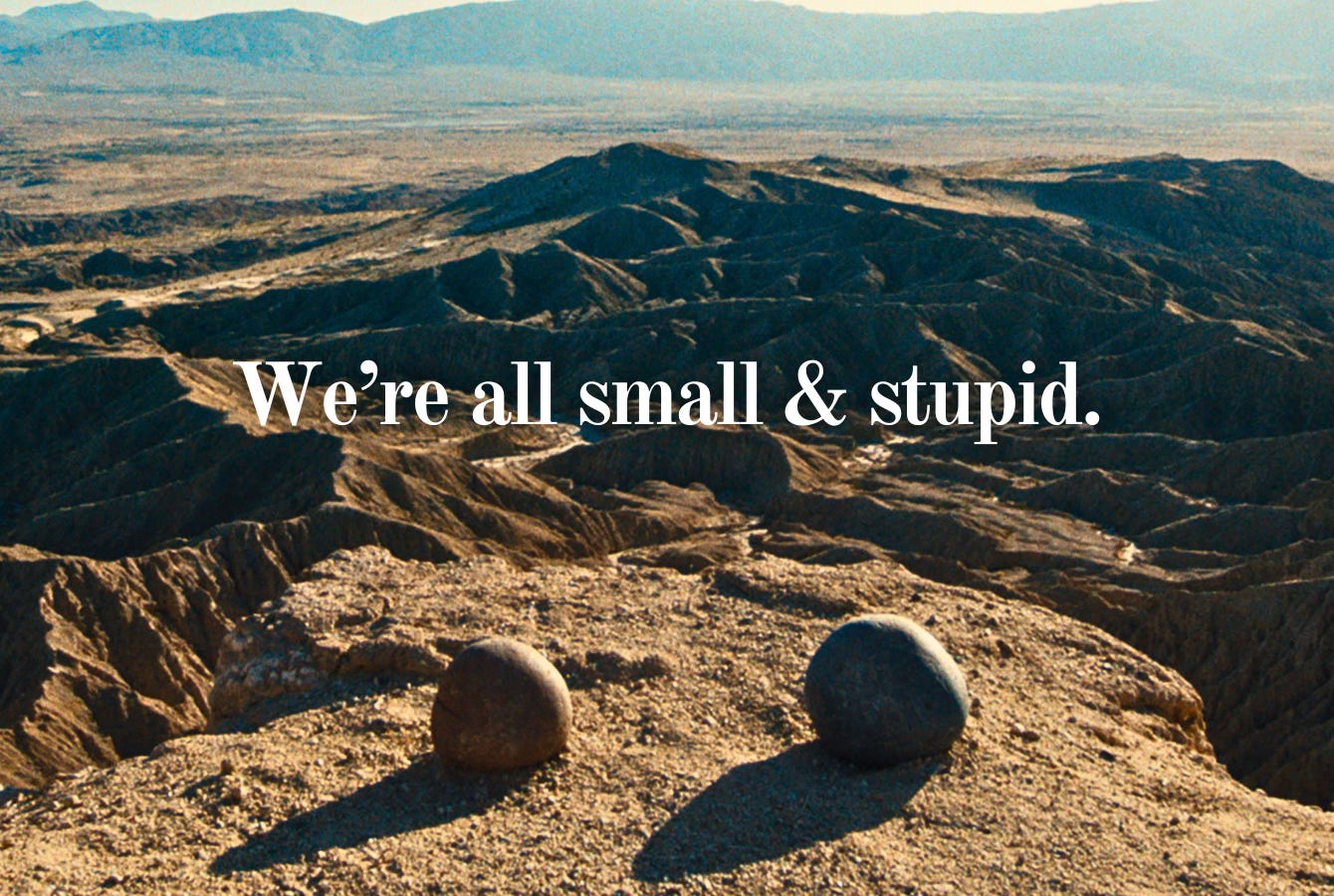

An insignificant pocket of an indifferent universe populated by machines driven by selfish genes. This worldview grew out of a series of scientific and philosophical discoveries that, one by one, overturned our ideas of human uniqueness. Copernicus removed us from the centre of the cosmos; Darwin unseated us from any kind of evolutionary “pinnacle”; the science that emerged from his theory placed us in nature as one animal among many. I forget who wrote it, but I once read that every time we name a feature as distinctly human, we go and discover it in another animal species. In the film Everything Everywhere All At Once, there’s a quietly devastating scene where a depressed character says:

“For most of our history, we knew the Earth was the center of the universe. We killed and tortured people for saying otherwise. That is, until we discovered that the Earth is actually revolving around the Sun, which is just one sun out of trillions of suns ... Every new discovery is just a reminder we’re all small and stupid. And who knows what great discovery is coming next to make us feel like even smaller pieces of shit.”

As I said, who hasn’t heard the materialistic, mechanistic view of life before, even if not expressed quite as baldly or as nihilistically as this? I even endorsed it for many years with the self-congratulatory air of the new atheists, committed to capital-T Truth however ugly it might be. Even so, when I read O’Malley’s version of the story, in which humans are “meat-bags that respond to stimuli”, I was inexplicably angry, and I almost wrote a response essay while in the fug of annoyance and outrage. Thankfully, I made myself sit for a few days and consider what my reaction said about my own worldview. Here’s what I noticed.

First, I took issue with his exorcism of the ghost in the machine, that thing we poetically call the “soul”. In spite of that indignance, and although I’ve moved away from the strict materialism of my youth, I still refuse to argue without evidence to support my claims. And the soul isn’t something for which I have exhibits A and B for evidence, or demonstrably true premises that lead inexorably to the conclusion that humans are more than mere matter. It is, instead, a descriptive term to acknowledge something I recognise in my first-person experience of being human. If I had an empirical justification for the human soul, my wrestling with religion would be a lot easier.

What I know for certain is that I really don’t like to think of myself and the people I love — hell, even the people I don’t much like — as robots responding to stimuli with algorithmic calculations, rather than with feeling and subjectivity. Of course, my unease with a proposition has no bearing on whether it’s true or false. So I went back to O’Malley’s article and scoured it again. This time, I paid more attention to his cat.

O’Malley writes about an episode in which his cat freaked out and behaved aggressively toward him and his partner. It turned out the cat was experiencing something called redirected aggression. “She was confused about what was upsetting her,” O’Malley writes, “and she had directed her anger at us instead.” Here, I realised why I’d been so irritated with what I’d read: it scared me. My anger was simply misdirected fear that O’Malley and the “rationalists” might be right, and that I might be wrong. It was anxiety about the idea that there might be nothing special about humans or the things we create.1

I’d experienced this anxiety before, when considering the current and future impacts of AI. I’ve thought about plugging some of my essays into one of the AI models and asking it to “write” an essay of its own, in my style. But I’ve never had the nerve to do it. The chance (however slight) that ChatGPT might be able to “do” what I do, that I could discover that there’s nothing inherently me about my writing, that a soulless machine could produce what took me weeks of writing and months of research and a lifetime of sweat and suffering and joy to conjure — the truth is, I don’t know how I would face that.

O’Malley is right to notice the muted response to the new AI music tools; I want to highlight a lack of response to how AI might challenge us existentially. I don’t mean in the sense of annihilating our species (which is worth considering and is being widely debated), but in the sense of disrupting yet more of what we take to be uniquely human. I don’t think we’ve been taking seriously enough the prospect of what it means for us — emotionally, spiritually, culturally — to learn that there is nothing that distinguishes human art from AI “art”. What will it do to us if we discover that it isn’t only the people “further down the corporate food-chain” (as O’Malley puts it) whose work can be largely replaced by AI, but that AI can produce higher-level cultural artefacts that meet our human needs?

To be clear, I’m not claiming AI ever will be able to produce art of the kind that humans can create. I’m personally unconvinced by the proposition — but largely because I take the existence of the numinous and of a transcendent realm within us as a tenet of informal faith. I therefore can’t be certain that AI will never be able to replace human artists. And I think anxiety of this kind, justified or not, sits beneath much of our thinking about the future of AI. That’s why we need to be talking about it much more openly. We keep scrambling to make sense of our situation after each crisis has tipped us on our heads and shaken the meaning out of our pockets. This time, let’s think about the consequences before our humanity is upended again.

There’s more to be said against the mechanistic worldview, and much to be argued in favour of what might be considered a poetic way of approaching life, and I plan to tackle those things in an upcoming essay. For now, I simply want to accept and assess that anxiety I’ve been feeling recently in the face of AI advances.