Azar Nafisi: The Magic of Fiction

On the transformative power of literature and the meaning of "upsilamba".

Welcome to “Words of Wisdom”, a series that zooms in on a passage of writing — an essay, a chapter, a speech — from a great thinker on a specific idea.

Today, Azar Nafisi: one of those writers whose pen can switch with ease from sharp and incisive to elegant and heartfelt. Not only does she write compellingly on living a life of literature — in a manner that convinces the mind and moves the soul — she has lived out her principles with admirable courage, never allowing philistine censors or theocratic bullies to stifle her belief in the magic of books.

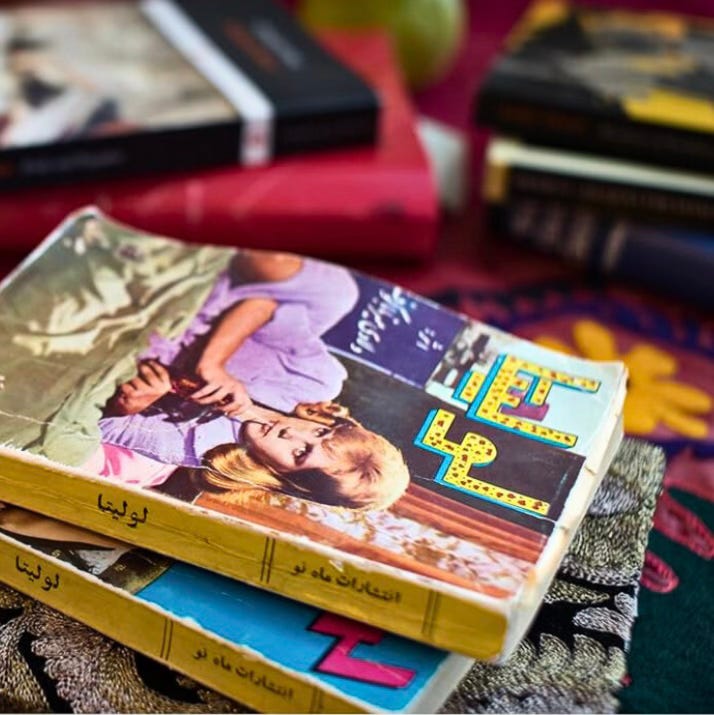

Here, I take a close look at her memoir, Reading Lolita in Tehran.

What do you think of when you think of Iran? Much of what I imagine comes from the books of fierce and poetic thinkers who describe the contradictions of that fascinating land.

I think of mountains and dry heat and the swirling steam of tea, and Azar Nafisi lends me the words that shape this picture. She writes of Tehran’s “mountains and its dry yet generous climate, the trees and flowers that bloomed and thrived on its parched soil and seemed to suck the light out of the sun”. Of daily life, she tells us, “Brewing and serving tea is an aesthetic ritual in Iran, performed several times a day”:

“We serve tea in transparent glasses, small and shapely, the most popular of which is called slim-waisted: round and full at the top, narrow in the middle and round and full at the bottom. The colour of the tea and its subtle aroma are an indication of the brewer’s skill.”

Of course, I also think of the theocratic repression Iranians live under, as indelible a part of the national picture as it is inescapable for those who suffer under its rule. I see in my mind the dark ink drawings in Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis, her singular depiction of the Islamic Revolution and the changes it brought to the lives of ordinary Iranians. I cannot forget what Christopher Hitchens wrote on the horrors of Iran’s theocracy, describing the state as one where:

“virgins are raped before execution because the Koran forbids the execution of virgins; where the censor cuts Ophelia out of the Russian movie version of Hamlet; where any move that a woman makes can be construed as lascivious and inciting; where goatish old men can be gifted with infant brides; and where the age of ‘consent’ is more like nine.”

I’m conscious of the fact that when I try to imagine an individual Iranian, he or she is usually an academic of some kind, living in a house full of books and sunshine, wryly and courageously defying tyranny with literature. This picture is entirely the product of the kind of books I read. As a result, my mental portrait of Iranians is simplistic and broad-brushed. One day, I hope to flesh out the human nuances by actually visiting Iran. Until then, I avail myself of the magic portals that books open into the homes and lives of writers such as Azar Nafisi.

In fact, even that notion of books as a “magic portal” comes to me from Nafisi, from her memoir Reading Lolita in Tehran. Specifically, it comes in chapter five of her section on Nabokov, which opens with a strange surprise.

“Upsilamba!”

So begins the chapter, with Nafisi carrying a tray of tea into her living room, where a young woman joyfully throws the word at her “like a ball, and I take a mental leap to catch it”. The young woman is named Yassi, and she is one of the seven female students who gather every Thursday morning at Nafisi’s house to engage in criminal activity: they are there to read forbidden Western classics.

Having left her teaching position at the University of Allameh Tabatabai,1 Nafisi set up a small class of her favourite pupils in her living room, where they enjoyed a freedom unknown to them in the rest of their lives. Nafisi tells us about their first session together:

“All of us had been nervous and inarticulate. We were used to meeting in public, mainly in classrooms and in lecture halls. The girls had their separate relationships with me, but except for Nassrin and Mahshid, who were intimate, and a certain friendship between Mitra and Sanaz, the rest were not close; in many cases, in fact, they would never have chosen to be friends.”

Were it not for books, these women would not have formed their literary conclave and its subsequent solidarity. Their comradery deepens over the course of their sessions together, the novels each contributing to an emerging lingua franca. Which brings us back to Yassi shouting out, “Upsilamba!”

The word comes from Nabokov’s Invitation to a Beheading, described here by Nafisi:

“In this novel, Nabokov differentiates Cincinnatus C., his imaginative and lonely hero, from those around him through his originality in a society where uniformity is not only the norm but also the law. Even as a child, Nabokov tells us, Cincinnatus appreciated the freshness and beauty of language ...”

This unusual attention to words sets the protagonist apart from others, who (in Nabokov’s telling):

“understood each other at the first word, since they had no words that would end in an unexpected way, perhaps in some archaic letter, an upsilamba, becoming a bird or a catapult with wondrous consequences.”

Nafisi once taught Invitation to a Beheading to a class of largely incurious students. “No one in class had bothered to ask what the word meant,” Nafisi writes. She even set the word in a midterm exam, asking them to “explain the significance of the word upsilamba”. Almost none of them had a clue what she meant — none, that is, except for a handful of students who were auditing the class simply for love of literature. Among them were some of the women who’d later attend Nafisi’s home lessons.

These exceptional students turned out to be much like Cincinnatus C. in their curiosity and love of language. Yassi has a “pathological” love of playing with words and tells Nafisi, “As soon as I discover a new word, I have to use it, like someone who buys an evening gown and is so eager that she wears it to the movies, or to lunch.” Yassi later says that she associates the word upsilamba with a dance — “C’mon, baby, do the Upsilamba with me” — which is fitting for one who dances with language as she does, feeling it in her body as much as her mind.

The similarities don’t end there. The society of Nabokov’s novel, in which “uniformity is not only the norm but also the law”, sounds presciently close to Iran after the Islamic Revolution. Nafisi’s study group meet under the cloud of segregation, state-sponsored misogyny, and repression of culture. In studying Western literature, these young women are guilty of “gnostical turpitude”, the crime that Cincinnatus C. is imprisoned for: knowledge of forbidden esoteric wisdom.

These correlations between the novel and real life are to be expected, given that the “theme of the class was the relation between fiction and reality”. The purpose of the meetings was to “read, discuss and respond to works of fiction” and discover how they “related to [their] personal and social experiences”. Nafisi adds:

“We were not looking for blueprints, for an easy solution, but we did hope to find a link between the open spaces the novels provided and the closed ones we were confined to.”

However, Nafisi urges her students to resist imposing reality on the novel. On the first page of Reading Lolita in Tehran, Nafisi cautions us against making too much of similarities between the world on the page and the world in which we live:

“Do not, under any circumstances, belittle a work of fiction by trying to turn it into a carbon copy of real life; what we search for in fiction is not so much reality but the epiphany of truth.”

To “belittle” the work of fiction means, yes, to disrespect it, but also to shrink it down so as to fit within the small and closed world they occupy. To do so would be to negate the expansive, open-source nature of fiction, and to disenchant it of its magic. So, if the idea is not to read the book by the light of reality, what are they doing? Precisely the opposite — reading reality by the light of the books:

“We were, to borrow from Nabokov, to experience how the ordinary pebble of ordinary life could be transformed into a jewel through the magic eye of fiction.”

Nafisi chose the novels for the group because of “their authors’ faith in the critical and almost magical power of literature”. She tells the story of a young Nabokov during the Russian Revolution, refusing to be distracted from writing his solitary poetry by the sound of bullets and the view of bloody fights from his window. “Let us see,” Nafisi tells her students, “whether seventy years later our disinterested faith will reward us by transforming the gloomy reality created by this other revolution.”

To alter books so they fit reality — which the poor reader does to make simple sense of complicated themes he doesn’t understand, and the capricious censors of all tyrannies do to make fiction work in service to ideology — is to make literature smaller, narrower, meaner. To do as Nafisi shows us in her book, to bring the magic of fiction into the base reality of our lives, is to expand our world. We gift reality, at least temporarily, the powers of efflorescence inherent in our ever-unfolding books.

This is what makes readers so like Scheherazade in A Thousand and One Nights, the first work the group reads. In the story of a “cuckolded king who slew successive virgins as revenge for his queen’s betrayal”, Scheherazade avoids the same fate by turning to storytelling, preventing the king’s violence with each tale she enchants him with. In doing so, she “breaks the cycle of violence by choosing to embrace different terms of engagement”. Little wonder that Nafisi thought such a story might have resonances with their condition as readerly women trapped in a violent tyranny. Scheherazade’s great magic, which her story and all stories grant readers, is this:

“She fashions her universe not through physical force, as does the king, but through imagination and reflection.”

We can wax a little too poetic about such things, so it’s important to note the very real ways that storytelling actually does allow us to shape our world. Humans have been called a “storytelling species” and for good reason: we seem to thrive in the world only when we’ve woven together its brute facts with causality (plot) and humanising its elements (character). This is how life and death become stories.

Even the most unsentimental materialist finds himself dissatisfied with the “neurochemical cocktail” description of his bond with his child; we prefer (perhaps need) the narrative of memory that turns parental love into a causal part of the story we and our children are living through. Hard-headed rationalism often convinces us that marriage is a mere legal document predicated on taxes, until we discover its deeper meaning and profound joy, and we take our place in the human story that, yes, evolves over time but also is rooted in the traditions of our oldest stories.

Asked why we avoid death, few would simply point to our in-built aversion to dying, that animalistic urge to stay alive; we instead tell a story about how our loved ones would mourn our death, and about losing the hypothetical future joy we imagine for ourselves. We use storytelling terms like “unfair” and “tragedy” — a sure sign that a person is thinking literarily rather than literally about the nature of the cosmos.

Nafisi lays out the relationship between storytelling and reality quite succinctly:

“We speak of facts, yet facts exist only partially to us if they are not repeated and re-created through emotions, thoughts and feelings.”

Books make sense of who we are and the world in which we live. They make sense of the facts that surround us by transforming reality into something even more real. It’s easy to be glib about this. We often speak of books having a certain magic, but something rings hollow. Too easy, almost. A superficial, though reassuring, kind of charm substitutes the true, deep power of literature that Nafisi writes of. This is not the magic carpet of escapism, but the despot-deposing, society-shifting, individual-empowering transformations that begin with the written word.

Others find their own ways of navigating the crushing torments of a brutal world, but for Nafisi and her young women, as for me and perhaps for you, it’s not a trivial thing nor a flippant expression of a “quirky personality” to say that books help us survive. They are silent incantations that transform us into who we need to be when it matters, and that allow us to escape the confines imposed on our minds like Houdinis of the imagination. That is their magic, and it’s much more than just a trick.

Still wondering about upsilamba and its meaning? You can read all about it — including answers supplied by Azar Nafisi, her students, and my own tentative suggestion — in this paid-subscriber bonus essay:

Upgrade for only £5 a month to get access to that, as well as all other bonus essays and the full archive.

Nafisi once taught Literature at the University of Tehran, until she was expelled for refusing to wear the mandatory veil. Years later, she attempted to resign from the University of Allameh Tabatabai, but the university refused to recognise her right to resign. After she continuously failed to show up for work, they expelled her. Such are the bizarre machinations and mind games authoritarian states must engage in to keep its iron fist gripped tight around the people.

![[Bonus] Escaping McFate](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_140,h_140,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F46eeb000-dfeb-469b-9733-0f5aa827d2b9_1340x900.png)

Thank you for this essay. You reminded me of what I loved about Nafisi's book. I keep thinking about the trial of The Great Gatsby that she set up in response to students' complaints, and how the deeper thinking about what and who was being put on trial became a new kind of danger. And by "danger" I mean thinking, because the link between reading and the ability to think new things and change your mind is so palpable throughout this book.