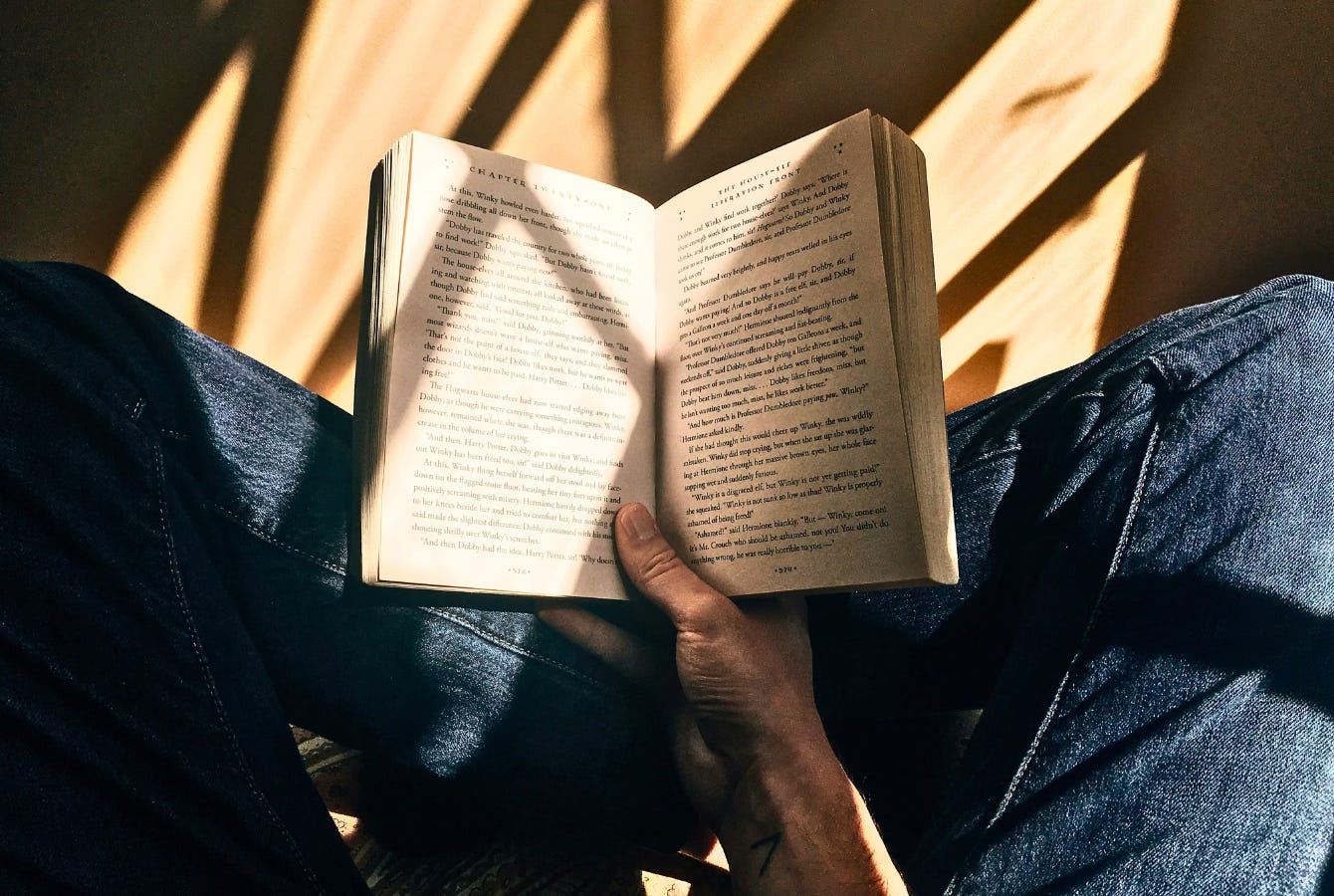

A Day in Reading

On why we read, where we read, and how reading can change throughout the day.

SUNRISE

Today, I wake with the sunrise. Its light tells the resurfacing mind that it must return from the peace of sleep to the brilliant pace of day. Lawrence Durrell paints a sunrise on the waking page of Bitter Lemons (1957), one that looks “as if some great master, stricken by dementia, had burst his whole colour-box against the sky to deafen the inner eye of the world”. At first, I resist the sunrise and tell myself that I will determine what time I’ll roll from deep slumber to caffeinated consciousness. Then the alarm clock begins screaming like a drill sergeant.

For Nabokov, in King, Queen, Knave (1968), the clock actually breathes life into the world. His book opens with a “huge black clock hand ... on the point of making its once-a-minute gesture; that resilient jolt will set a whole world in motion”. As the dial turns to the number that signifies — arbitrarily and yet meaningfully — the start of another day, “iron pillars will start walking past ... the platform will begin to …